Chinese Calligraphy — Evolution, Scripts, Aesthetics, and Appreciation of Ancient China's Supreme Art

Chinese Calligraphy, or Shufa, encompasses all the methods of writing Chinese Characters or Hanzi throughout history.

It has been considered the supreme visual art in ancient China and remains a popular art form practiced by many people today.

Thanks to calligraphy art, tens of thousands of square Hanzi (Chinese characters) have transformed into expressive images that carry stories, emotions, and rhythms dancing with beautiful music and poems.

Calligraphy Artwork by Zhao Mengfu (1254 — 1322) — Palace Museum (Photo by Dongmaiying)

Why Is Chinese Calligraphy the Supreme Art in History?

Throughout history, there have been over 100,000 Chinese characters, and approximately 3,500 are commonly used, covering 99% of today's reading materials.

The shape, thickness, and position of each stroke, as well as the outlines, sizes, and structure of each character, along with the rhythm, composition, and layout of a whole article, encompass tens of thousands of changes and possibilities for writers to express creativity.

This complexity makes Chinese Calligraphy a beautiful visual art.

One of the Greatest Calligraphy Art "Lanting Jixu", Written by Great Chinese Calligrapher Wang Xizhi (303 — 361). This Facsimile Version was Copied by Callihraphor Feng Chengsu (617 — 672) and Preserved in Palace Museum.

What made calligraphy the supreme art was the group that wrote and appreciated it in ancient imperial China: the nobles and scholars.

Aristocrats and scholar-officials, the ruling class of ancient imperial China, could get good educations to read and write, afford calligraphy sets, and have enough leisure time to practice.

Meanwhile, handwriting has been considered an important representation that conveys one's personality, temperament, educational level, elegance, morals, and wisdom.

Therefore, calligraphy, the means and laws of writing, was the ruling class's most essential and popular art form in ancient times.

Calligraphy Work Written by Emperor Taizong of Tang in the Year 646, to Memorize Their Rise in Rebellion Here and to Pray for Blessing to the Tang Empire — Stele in Jinci Temple of Taiyuan City

Uses of Chinese Calligraphy Art

Oracle, Bronze, and Stone Inscriptions — To record history and to eulogize epic achievements, remarkable reigns, ambitious decrees, or beautiful sceneries.

Oracle Bone Inscription or Jiagu Wen During the Reign Period of King Wu Ding (? — 1192 BC), the Extant Earliest Chinese Writing — National Museum of China

Letters, Articles, and Poems on Bamboo Slips, Silk, and Paper — To communicate, write, record, and convey as the written language.

Plaques or Paibian — To note locations, commemorate events, or convey belief and culture.

Plaques or Paibian Hanging on Pagoda of Fogong Temple (Ying Xian Mu Ta), the Most Ancient (Built in 1056) and Tallest Wooden Tower (67.31 meters) in the World. The Top One was Written by Yongle Emperor (1360 — 1424), the Second Was Written by Zhengde Emperor (1491 — 1521).

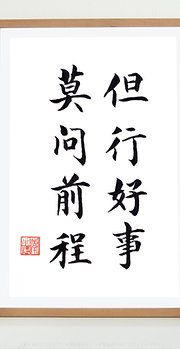

Screens, Fans, and Scrolls — To decorate and express one's elegance, ambition, talent, and social status.

Seals — To show status as signatures, from emperors to civilians, from governments to personal studios.

Jade Seal of Prime Minister Wang Xijue (1534 — 1611) of the Ming Dynasty — Suzhou Museum (Photo by Dongmaiying)

Epitaphs — To memorize and record the life experiences and achievements of decedents.

Epitaph from the Mausoleum of Yuan Gongyu, Wrote by Remarkable Prime Minister Di Renjie (630 — 704) — Qian Tang Zhi Zhai Museum in Luoyang City (Photo by Dongmaiying)

History, Evolution, and Scripts of Chinese Calligraphy

From the utilization of the Oracle Bone Inscriptions during the Shang Dynasty (1600 BC — 1046 BC) till today, there are five main script styles in Chinese Calligraphy art: Seal Script (Zhuanshu), Clerical Script (Lishu), Regular Script (Kaishu), cursive script (Caoshu), and Semi-cursive script (Xingshu).

Seal Script or Zhuanshu

Seal Script includes two types: Large Seal Script (Dazhuan) and Small Seal Script (Xiaozhuan).

Large Seal Script or Dazhuan refers to writing systems before the Qin Dynasty (221 BC — 207 BC), mainly including Oracle Bone Scripts (Jiaguwen) of the Shang Dynasty (1600 BC — 1046 BC), and Bronze Inscriptions (Jinwen) that became popular from the late Western Zhou Dynasty (1046 BC — 771 BC) to the Warring State Period (403 BC — 221 BC).

Bronze Inscriptions on Ding of Duke Mao (Mao Gong Ding) — Taipei Palace Museum (Photo by Dongmaiying)

Small Seal Script evolved from and simplified the Large Seal Script, and was promoted as the official writing system of the unified Qin Dynasty (221 BC — 207 BC), under the command of Qin Shi Huang (259 BC — 210 BC), the first emperor of China.

It stopped being the official writing system in the late Western Han Dynasty (220 BC — 8 AD).

However, because of its ancient style and beautiful structure, Small Seal Script characters have been widely used in calligraphy, seal carving, and stone inscriptions.

Small Seal Script Characters in Rubbing of Yishan Stele That Records and Praises Accomplishems of Qin Empire, Written by Chancellor Li Si (284 BC — 208 BC) the Creator of Small Seal Script — Beilin Museum of Xi'an

Clerical Script or Lishu

Evolved from the Seal Script by clericals, the Clerical Script or Lishu with straight strokes is easier and faster to write.

It originated in the Qin Dynasty (221 BC — 207 BC), thrived in the Han Dynasty (202 BC — 220 AD), and was popularized until the end of the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420 — 589).

In calligraphy history, artworks of the Han Dynasty (202 BC — 220 AD) are believed to be the peak of the Clerical Script or Lishu.

Clerical Script or Lishu Characters on Debris (Xi Ping Shi Jing) of Official Confucianism Classics Carved on Stone (175 — 183) — National Museum of China (Photo by Ayelie)

Regular Script or Kaishu

Regular Script, or Kaishu, evolved from the Clerical Script and has been the most popular and common script style from its invention in the late Han Dynasty (202 BC — 220 AD) until today.

In traditional Chinese Calligraphy aesthetics, works of the Tang Dynasty (618 — 907) are believed to be the most eminent and valuable of Regular Script or Kaishu art.

Regular Script or Kaishu Characters in Rubbing of the Duobaota Stele Written by Great Calligrapher Yan Zhenqing in the Year 752 — Beilin Museum of Xi'an

Cursive Script or Caoshu

Appeared in the early Han Dynasty (202 BC — 220 AD) and based on Clerical Script, the Cursive Script or Caoshu is the fastest calligraphy style to write, which is relatively simple but hard to recognize.

Cursive Script or Cao Shu Characters in Part of Calligraphy Work "Thousand Character Classic", Written by Emperor Huizong of Song (1082 — 1135) — Liaoning Museum

Semi-cursive Script or Xingshu

Semi-cursive Script, or Running Script, in Chinese Xingshu, appeared in the late Han Dynasty (202 BC — 220 AD) and evolved from the Clerical Script.

It could be written faster and smoother than the straight Regular Script style and is easier to recognize than the Cursive Script.

Semi-cursive Script or Xingshu Characters in Calligraphy Work "Hanshi Tie", Written by Eminent Scholar Su Shi (1037 — 1101) of the Song Dynasty — Taipei Palace Museum

Basic Rules and Appreciation of Chinese Calligraphy

Strokes

Strokes, the most fundamental elements of a Chinese character, should follow the basic order to write: from top to bottom, left to right, inside to outside, and horizontal to vertical.

Each stroke's shape, thickness, position, and flow differ in each script style and writer, such as neat and decorous for Regular Script, creative and smooth for Cursive Script, etc.

Structure

Strokes constitute Chinese characters following specific structures, which in writing, are required to be stable and delicate, balanced but with rhythm, with focused yet contrasting elements.

Part of Calligraphy Work "Semi-cursive Script or Xing Shu Thousand Character Classic", Written by Ouyang Xun (557 — 641) — Liaoning Museum

Composition Art

Including the arrangement of all characters, lines, blank, and signs, the seal designs should be composed as an artwork in harmony while keeping their brilliant features, like the dynamic, dancing rhythms, in the balanced and smooth flows.

Use of Calligraphy Brush

Because of the flexibility of the calligraphy brush, the writer's wielding speed, exerting pressure, and characters' fluidity together form the flow of the artwork and convey the story and emotion behind the artwork.

Part of Calligraphy Work "Luoshen Fu", Written by Zhao Mengfu (1254 — 1322) — Palace Museum

Use of Ink and Water

The concentration of ink, and the ratio of ink and water, are essential factors that influence a calligraphy artwork's thickness of colors and dryness of brush strokes.

Based on the written content and emotion, each calligrapher has different arrangements regarding ink and water to make dynamic and harmonious changes between dry and wet, heavy and light.

Excellent Use of Ink in Calligraphy Work "Kusun Tie", Written by Huai Su (737 — 799) — Shanghai Museum

The Four Treasures of the Study and Other Chinese Calligraphy Supplies

To write calligraphy works, Four Treasures of the Study (Wen Fang Si Bao) are the necessary supplies, including brush, ink, paper, and inkstone.

Other tools could also help to practice calligraphy, such as paperweights, brush hangers, brush holders, brush washers, seals, and ink paste.

Chinese Calligraphy Supplies, Picture from Zou Feng.

Main Steps to Practicing Chinese Calligraphy

In general, calligraphy practice includes four procedures.

-

To learn the proper posture to hold the brush, get familiar with the thickness and absorbency of paper, practice the use of ink and water, and experience the movement and pressure of the brush on different strokes.

-

To copy different calligraphy scripts, usually model on artworks of each style's most famous Chinese calligraphers.

Generally, Regular Script or Kai Shu is the most recommended style for beginners, but people can start with Clerical Script, Li Shu, or other types they favor.

Cursive Script, or Cao Shu, is accepted as the most challenging style to write well, so it is usually for people with proficient calligraphy skills to practice.

In this step, from copying those masterpieces, one can learn the use of brushstrokes, structure, and composition of characters, and how they express emotion, faith, and story through written characters.

Regular Script or Kai Shu Characters in Rubbing of the Shen Ce Jun Stele Written by Great Calligrapher Liu Gongquan (778 — 865) — National Library of China

-

To write independently, by imitating the styles of calligraphers that one achieved proficiency from the last step, to see if one gained the spirit of calligraphy from established masters.

-

To create and form your calligraphy style based on knowledge and rules learned from ancient masterpieces.

Copper Writing Brush Holder (Bi Shan) of the Ming Dynasty (1368 — 1644) — Wuzhong Museum (Photo by Dongmaiying)

You Might Also Like:

Chinese Symbols — Cultural Meanings and Aesthetic Values

Chinese Characters — Origin, Formation, and Meaning

Chinese Languages — History, Development, Classifications, and Fun Facts

Chinese Paintings — Tradition, Aesthetics, Poetic Beauty, and Artistic Conception

Chinese Poetry — Eternal Resonance in Poems To Chant and Appreciate

Imagery in Ancient Chinese Poems — Expressing Emotions through Visible Objects

Chinese Paper and Art — Paper Cutting, Oil Paper Umbrella, and Kite

Chinese Porcelain and Pottery — Art of Earth and Fire

Chinese Silk — Traditions, Utilizations, Fabrics, Embroideries, Products, and Art

Chinese Fan — History, Classification, Utilization, Art, Culture, and Artifact

Chinese Art — Aesthetic, Characteristic, and Form

Timeline of Ancient Chinese History

Famous, Influential Figures in the History of China

Schools and History of Ancient Chinese Philosophy

Color Symbolism in Chinese Culture

Chinese Patterns — Ultimate Introduction to Origin, History, Meaning, and Culture

Chinese Architecture — Tradition, Characteristics, and Style

Chinese Furniture — Oriental Artwork with Aesthetic and Practical Values

Chinese Music — History, Classifications, Artists, Eminent Songs, and Fun Facts

Traditional Muscial Instrument

Chinese Dance — Ancient Art Form Across Time and Space

Shadow Puppetry and Puppet Show — Magnificent World of Art of Fingertips

Traditional Handicrafts in Chinese Art